The Vinland Map Part VI: An Analysis of The Tartar Relation

Taken from notes by George D. Painter and expanded upon by your author

Like its companion, the Vinland Map, The Tartar Relation has remained unknown since the late Middle Ages. The manuscript is vital to interpreting the Vinland Map, as it appears The Tartar Relation was one of the main sources for the Asian section of the Map. Aside from the Map, however, The Tartar Relation is important and interesting in its own right as a primary source on the Carpini mission to Asia from 1245 to 1247 and an example of, or European interpretation of, the history and folklore of the Mongols at the height of their empire.

The Origins of The Tartar Relation:

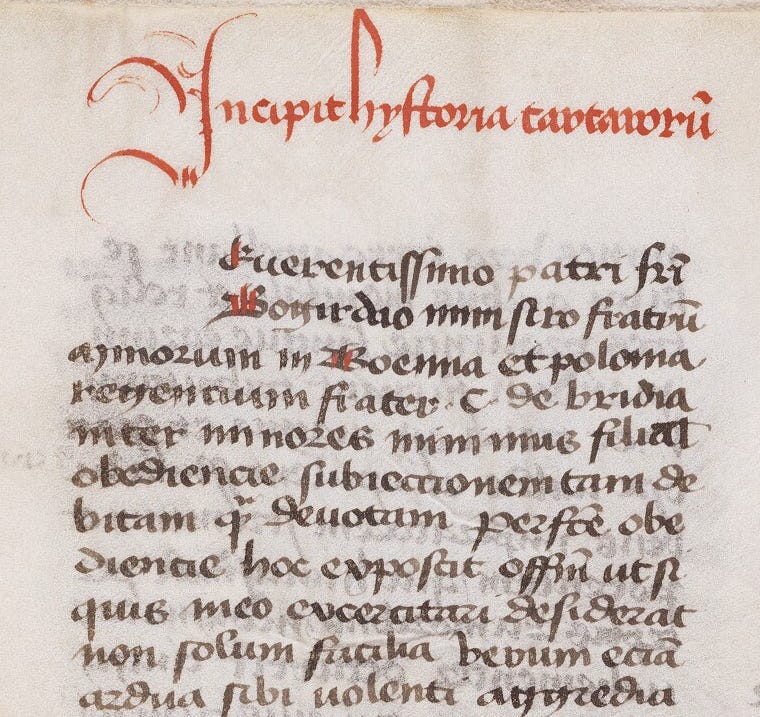

On July 30, 1247, a Franciscan friar known to history only as C. de Bridia finished an intelligence report on the Tartars (or Mongols to use their more familiar name) which he had spent the previous few weeks compiling. C. de Brida composed this report at the request of his superior, Friar Boguslaus, then head of the Franciscan Order in Bohemia1 and Poland. A Franciscan mission had been sent to the Mongols two years previously, departing from Lyon, France on April 16, 1245, and the participants were passing through Poland on their way back. The leader of this mission was Friar Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, or in English, John de Plano Carpini. Friar Carpini was originally from Umbria in Italy and had been a disciple of St. Francis of Assisi. Traveling with him were two companions, Benedict the Pole and Ceslaus of Bohemia. C. de Bridia states he gained the material for his manuscript from all three of these but mostly from a draft of a report composed by Friar Benedict and from Benedict’s own comments on the mission. Rather than an account of the friar’s journey, de Bridia’s report is on the history of the Mongols and their conquests, as well as their character, way of life, social and religious customs, and methods of warfare. This information was of vital importance to Eastern Europe at the time. Six years earlier, in 1241, the Mongols had invaded Poland, Silesia2, and Hungary bringing shocking destruction and bloodshed, and had more recently announced their intention to return and conquer all of Europe. De Bridia titled his report “Historia Tartarorum” or “Description of the Tartars”, more familiarly known now as The Tartar Relation. A copy of this report would of course later be bound with the Vinland Map and end up in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale.

Three other reports of Carpini’s mission were issued the same year and are well-known to history. Two were written by Carpini himself. The first was “Historia Mongalorum[sic] quos nos Tartaros apellamus” (Description of the Mongols whom we call Tartars) which was distributed to interested parties in Poland, Bohemia, Germany, Liége3, and Champagne between June and November 1247. This account is in eight chapters of the same subjects covered in The Tartar Relation but in an expanded version. Carpini’s second version of this report was composed after his arrival in Lyon in November 1247. It is the same text as his first version, with 31 minor additions and ninth chapter containing Carpini’s account of the journey to Karakorum (the capital city of the Mongol Empire) and back. The third report is Benedict’s own account of the journey, taken down in dictation at Cologne near the end of September 1247. Benedict’s account is now only found in two manuscripts of Carpini’s first report, where it precedes Carpini’s text and has no independent title.

When Carpini and his companions were on their mission, Friar Vincent of Beauvais was already at work on his Speculum Maius (recall our discussion of him in the previous publication). Vincent was frequently in the court of Louis IX, King of France, later Saint Louis. Early in 1248 Pope Innocent IV sent Carpini to Louis to request that he postpone his departure on what would be the Seventh Crusade (1248-1252). Based on Carpini’s report, Pope Innocent likely feared the Mongols were planning to attack Europe soon and believed Louis would be needed to defend Christendom in Europe. Carpini was unsuccessful in persuading the king to delay, but Book XXXII of Speculum Historiale, the final book of that work, contains a narrative of Carpini’s journey. No doubt Vincent gained a manuscript of Historia Mongalorum at that time, or perhaps an oral account of the journey from Carpini himself.

The Discovery of a Second Copy of The Tartar Relation:

Since its appearance in 1957 alongside the Vinland Map, it was believed The Tartar Relation was the only surviving manuscript of C. de Bridia’s report of Carpini’s mission. However, a second copy was discovered in 2006 at the Lucerne Central and University Library, and is believed to date from between 1335-1340, making it about a century older than the Vinland Map copy. The manuscript in Lucerne was also bound with the Speculum Historiale, like the two manuscripts that were once bound together with the Vinland Map. This indicates that pairing the two manuscripts together did not originate with the scribe who created the 1440 manuscripts with the Vinland Map. This copy of The Tartar Relation was catalogued in Lucerne as early as 1959, about two years after Laurence Witten acquired the more famous edition.4 Unlike the companions to the Map, we know the scribe and a partial history of the older copy. It was completed by Hugo de Tennach who was employed by Peter of Bebelnheim, a teacher in the Cathedral of Basel. Hugo de Tennach produced not only The Tartar Relation manuscript but the whole of Speculum Historiale in four volumes. The Tartar Relation is bound with the fourth volume, and these all belonged to the Pairis Abbey (in modern-day Alsace, France) until 1420 when they were pawned to the St. Urban’s Abbey in Lucerne. While it is possible the Yale Tartar Relation and Speculum Historiale are copies of the Lucerne versions, it is more likely both are copies of a separate, earlier document.

But how did these two manuscripts come to be together in the first place? Certainly it seems that a scribe copying Speculum Historiale who was also familiar with The Tartar Relation was impressed by The Tartar Relation being a relevant addition to Book XXXII of Speculum Historiale and placed them together. This must have happened sometime between when Speculum Historiale was completed in 1255 and 1340 when the Lucerne copy was produced. This could not have been Vincent de Beauvais himself, as he was not known for adding documents verbatim to his own work. His method was to use his own summaries or descriptions from other sources.

In its current state, the Yale manuscript of Speculum Historiale consists of 239 leaves in 15 quires of 16 leaves each. The quires are labeled e-t and contain books XXI-XXIV of the Speculum Historiale. The first leaf of quire e and the preceding four quires (a-d) appear to be missing. Calculations of text size, word count, and available space show the missing 65 leaves would have been sufficient material for the table of contents and text of book XX and the missing table of contents for book XXI. It seems likely that this manuscript originally contained books XX-XXIV of Speculum Historiale. At the end of book XXIV is a colophon: Explicit tertia pars speculi hist “here ends part three of the speculum historale”. Recall the note found on the back of the Vinland Map: Delineatio Ie partis, 2e partis, 3e partis speculi “Delineation of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd part of the speculum”. Let us follow this chain of evidence to a conclusion

First, The Tartar Relation is linked by its subject matter to the final book of Speculum Historiale , book XXXII. It has nothing to do with the books which formed the Yale manuscript (books XXI-XXIV) to which it was originally bound based on physical evidence (see your author’s previous publications in this series). If this manuscript of Speculum Historiale was originally completed with a final volume, now lost, which contained the last eight books of the work, The Tartar Relation should have been placed after them at the end of Book XXXII rather than after Book XXIV as it was in the Yale manuscripts.

Second, the Vinland Map, based on the colophon on its reverse, was intended as an illustration of Speculum Historiale, is also out of place in a volume which contains only Books XX or XXI-XXIV of the work. It would be better placed at the beginning of Speculum Historiale, before Book I, or in the last volume along with its close companion in subject matter, The Tartar Relation.

Third, the colophon on the Vinland Map “Delineation of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd parts of the Speculum” conflicts with the colophon at the end of the Speculum Historale manuscript “Here ends the third part of the Speculum Historiale”. If the “third part” of both documents references the same thing, then the Vinland Map should belong to a final volume of Speculum Historiale, containing the last seven books.

Fourth, the colophon at the end of the Yale Speculum Historiale is inconsistent with itself if the “third part” was intended to reference the end of a manuscript of this work. Counting the supposed missing quires (a-d) and two leaves for the Vinland Map and 16 leaves for The Tartar Relation, the original volume would have contained 21 quires and a total of 322 leaves. Based on text size and available page space, if the preceding books of Speculum Historiale, Books I-XIX were also originally part of this manuscript, they would have required about 1,100 leaves, or two “parts” or volumes of about 550 leaves each. Why would the “third part” of Speculum Historiale then only consist of 304 leaves? It seems unlikely, based on this idea, that the Yale manuscript could be a “third part” of the full Speculum Historiale text.

This of course all depends on the meaning of the word “part”. The only division of the full text of Speculum Historiale is into thirty-two “books”; Vincent did not divide it into “parts” or any other method of division. The full text of Speculum Historiale is approximately 1,450,000 words and was only occasionally produced, via large folios and small text, as a single volume. Usually, both in manuscript and print form, it was broken down into multiple volumes of more manageable size, which were often called “parts”. At the end of each manuscript volume, as a guide to both binders and readers, the scribe would add the colophon “Here ends the first (second/third/etc.) part…”. It is most likely, considering this, that the Vinland Map was originally intended to illustrate a three-volume manuscript of Speculum Historiale and the title indicates the Map is a “delineation” (delineatio) to illustrate the whole work. The original Vinland Map, of which ours in question is possibly a copy, may have been in the first volume, at the beginning, and the end of the third volume was bound a manuscript of The Tartar Relation.

The word “part” confused the scribe producing our manuscript copy as much as it has modern researchers. He mistook it as a genuine textual division intended by the original author, rather than a reminder for binders and readers of various copies, and copied it as such. Our scribe, or perhaps even a predecessor he was copying from, likely copied from a four-volume text in which Book XXIV was the end of the third volume. Recall that the manuscript of Speculum Historiale and The Tartar Relation discovered in Lucerne also divided Speculum Historiale into four volumes. (It is unfortunate this volume did not also contain a map which could have vindicated Vinland Map believers.5) Evidently, the binder made the same error and inserted the Vinland Map and The Tartar Relation not in the last volume (where they should have been, based on their subject matter) but in the “third part” of the manuscript.

The Original Source Of the Yale Tartar Relation:

Based on the text size and calculations of required space from the extant manuscript, along with the page indexing (e-t) of the quires, George Painter posited the Yale Speculum Historiale fragment was the fourth in a five-volume set of the work, with each volume containing six or seven books each with the fifth volume possibly containing the final eight books. Or maybe a situation where the fourth volume contained five or six books and the fifth seven books. That the Yale manuscript lacks signature letters v, x, y, and z, which would hold Book XXV of Speculum Historiale, strongly suggests the latter scenario. The binder was possibly very mistaken, even more so than the scribe who created the manuscript, and took the colophon “here ends the third part…” to mean book XXIV was the end of the volume and left out Book XXV.

If the Yale manuscripts are a copy of an earlier manuscript, or even a copy of a copy, did a previous edition also contain a map? Could that map also have shown Vinland? If the original source was a three-volume set of Speculum Historiale it could have been composed of larger folios to contain all the text in three books. If this is so, the Vinland Map may also have been in a larger format originally, which would account for the minute script in the existing copy. The small text of the Map then would be a necessary artefact of the map being “shrunk down” (for lack of a better term) to fit into the Yale folio size.

Could there possibly be still in existence a three-volume set of Speculum Historiale, bound with The Tartar Relation and a map depicting mysterious islands to the west named Vinland? As stated previously, researchers have accounted for approximately 250-350 manuscript versions of fragments of Vincent’s Speculum Maius, with Speculum Historale being the most popular section. If any had maps showing a particular part of the world included with them, they certainly would be known by now, one would hope. It has been 1,000 years since the Norse explored Vinland, over 700 years since Vincent finished his Great Mirror, over 600 years since the manuscript in Lucerne was completed, and over 500 years since the Yale manuscripts were completed. Since that time, many libraries and archives have been lost to the strife and iconoclasm of the Reformation, the chaos of the Revolutionary era, and the apocalyptic destruction of two world wars. Others, like the 15,000 volume library that once belonged to Ferdinand Columbus, were lost simply to the inevitable decay of time and neglect.6 If such a manuscript did at one time exist and has not yet come to light, then it is most likely lost to us now. Yet still, the manuscript in Lucerne, which is a century older than the Yale manuscripts, was not discovered until 2006, nearly 50 years after it was first cataloged. It is possible the original source manuscript still lies unrecognized or overlooked in a half-forgotten medieval archive.

Bohemia is the modern-day western Czech Republic

Parts of modern-day Poland, Czech Republic, and Germany

Modern Belgium

It is unfortunate that, though it was catalogued around 1959, the Lucerne TR manuscript was not identified until 2006. George D. Painter passed away in 2005 and would no doubt have appreciated knowing there was a second copy of a manuscript he had so carefully studied and defended.

What is a good term for those who believe the Vinland Map is a genuine Medieval artifact? Vinland Map Believers? Vinland Map Truthers? Vinland Map Authenticists/Authenticators?

Like Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum Maius, Ferdinand Columbus envisioned, and attempted to compile, a library that would be a source of universal knowledge.